Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose. There is no funding support for the production of this paper.

Abstract

Internal nasal valve collapse is a common cause of nasal obstruction. Butterfly grafting is a proven technique for repair of nasal valve collapse. This article will focus on nuances of butterfly grafting to both improve functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Introduction

Nasal valve collapse is a common cause of nasal obstruction. The internal nasal valve is the narrowest portion of the nasal airway and, therefore, subject to the highest resistance to airflow. It is bound by the nasal septum, the head of the inferior turbinate, and the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage (ULC). Narrowing of this angle or intrinsic structural weakness of its components results in increased resistance to airflow and nasal obstruction.

Medical therapy aims to improve the patency of the internal nasal valve by reducing mucosal inflammation. However, when valve collapse is due to structural narrowing or weakening of the internal nasal valve, medical therapy alone will not suffice.

Surgical treatment options are available to address each anatomic structure that contributes to nasal valve collapse. Inferior turbinate hypertrophy and septal deviation are addressed with inferior turbinate reduction and septoplasty, respectively. Surgical options that directly address the nasal valve include, but are not limited to, valvuloplasty, lateral suture suspension, cartilage grafting, absorbable nasal implants, and radiofrequency-induced thermotherapy.

This article will focus on the nuances of butterfly grafting for internal nasal valve collapse, a proven technique for internal nasal valve repair. Butterfly grafting utilizes auricular cartilage placed over the nasal valve to act as internal nasal strip. The graft stents the nasal valve, thus increasing the angle of the valve and reducing airflow resistance. This technique was originally described by Claus Walter in 1977 (1) and increased in popularity in the early 2000’s, partly in thanks to Clark and Cook (2). All patients experience symptomatic improvement and the vast majority have a resolution of symptoms (2-5).

The biggest criticism of the butterfly graft is its external visibility. Studies have shown that between 3-19% of patients who undergo butterfly grafting are dissatisfied with the cosmetic appearance (2-4). This cosmetic dissatisfaction is partly due to butterfly grafts tendency to increases the nasal width by an average of 6.4% (6). Due to the graft position and thickness, unfavorable supratip fullness and projection may develop (6).

Modifications have been described to mitigate these criticisms. Graft visibility may be limited by reducing its width, and graft function may be improved by lengthening the graft to extend to the piriform aperture (7). This paper will focus on nuances of the butterfly graft technique that may further increase its effectiveness while concurrently reducing external visibility.

Pre-operative assessment

The diagnosis of internal nasal valve is based on clinical history and physical examination. The typical history is significant for constant and persistent nasal obstruction. Symptoms may be exacerbated by physical exertion. Patients often experience little relief with nasal sprays, but may have improvement with externally-placed nasal strips. Anterior rhinoscopy reveals a reduced internal nasal valve angle and dynamic collapse of the valve with inspiration. The Modified Cottle Maneuver can help predict those who will improve with surgery (8). The maneuver is performed by placing a curette intranasally at the level of the internal nasal valve and applying gentle lateral pressure to support the valve. If the patient reports significant improvement in nasal obstruction, the result is positive, and the patient is considered a good surgical candidate. If there is concurrent mucosal inflammation or inferior turbinate hypertrophy, the patient should undergo a trial of medical management with nasal saline and intranasal corticosteroids. Nasal Obstruction Symptoms Evaluation (NOSE), a validated tool for assessing nasal obstructive symptoms, is performed pre-operatively. Pre-operative photo-documentation is obtained. In discussing surgical expectations with the patient it is important they understand that slight widening of the nasal dorsum is expected.

Non-delivery Endonasal Approach

The endonasal approach has fallen relatively out of favor in the recent decades, as the popularity of the open approach has increased. However, it remains a valuable option in rhinoplasty and is especially useful for the treatment of internal nasal valve collapse. The endonasal approach is classically divided into either non-delivery or delivery techniques. The delivery technique involves a combination of intercartilaginous and marginal incision so that the lower lateral cartilages may be literally delivered from the nose allowing for more extensive tip work. The non-delivery approach involves either an intercartilaginous or intracartilaginous incision only, both of which leave the lower lateral cartilages within the nose. For the butterfly graft, an intercartilaginous approach is used. This non-delivery endonasal approach allows for separation of the scroll region (junction of the upper and lower lateral cartilages) and exposure of the entire nasal dorsum for placement of the butterfly graft. The endonasal approach has the advantage of decreasing surgical dissection, thus reducing dead-space and limiting the risk of destabilization of the nasal tip support mechanisms. Additional advantages of the endonasal approach include shorter operative time, elimination of external scar, reduced of post-operative edema, and quicker recovery (9).

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed on the operating table and rotated 180 degrees. The eyes are taped with adhesive skin strips (Steri-Strip™, Nexcare™ 3M, St. Paul, MN). The entire face is prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. The nose is injected with a 50:50 mixture of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 and 0.25% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine in a typical rhinoplasty fashion. The vestibular skin is dried and the incision marked with a fin tip pen beginning laterally as an intercartilaginous incision then extending medially onto the anterior aspect of the caudal septum.

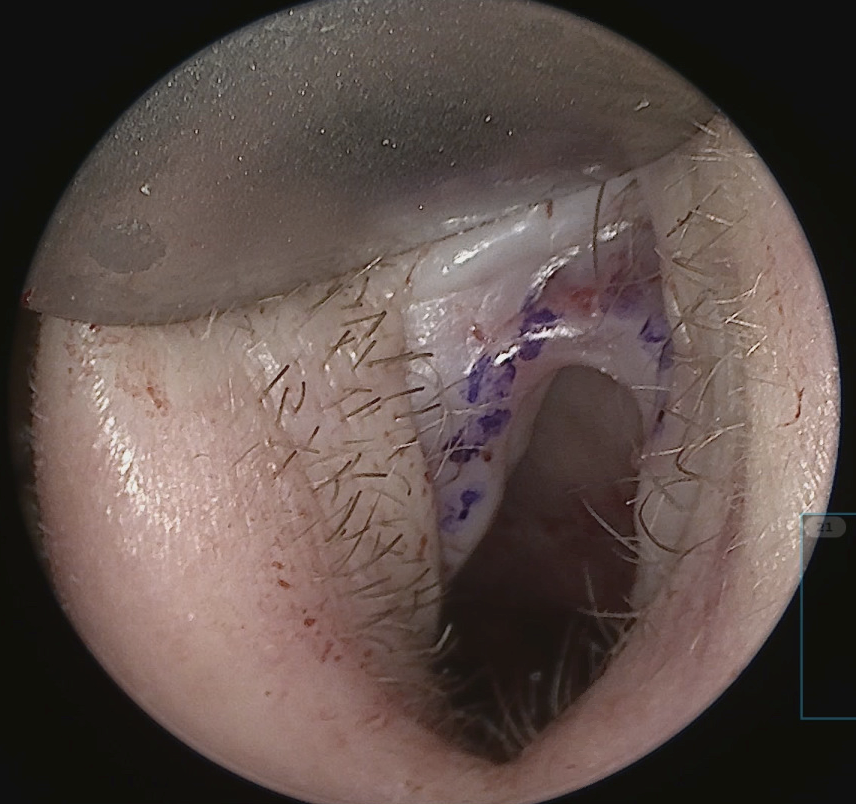

The intercartilaginous incision is made with a 15 blade beginning laterally and carried medially, taking care to stay caudal to the vestibular arch to reduce the risk of post-operative vestibular stenosis (figure 1). The incision is continued onto the anterior aspect of the caudal septum. While making the incision, a converse retractor in the non-dominant hand is used to evert and tense the tissue. The blade and converse retractor move in a synchronized fashion while progressing from lateral to medial to allow for optimal exposure and tension/counter-tension for a precise incision.

Dissection begins laterally with the goal of establishing the plane between the upper and lower lateral cartilages and staying superficial to the upper lateral cartilages. This can be challenging as the upper lateral cartilages have a tendency to furl under the lower lateral cartilages in the scroll region. “Unrolling the scroll” allows the surgeon to better visualize the free edge of the upper lateral cartilage and dissect in the appropriate plan. This is accomplished by retracting anteriorly with the converse retractor while simultaneously pushing the nasal skin posteriorly with the non-dominant middle finger, thus unfurling the cartilage.

With the correct plane established, dissection is continued lateral, cephalic, and medial to expose the dome. The same process is repeated on the contralateral side. The incisions are then connected over the caudal septum. Dissection is then carried over the dome and nasal dorsum until it is completely freed from the soft tissue envelope. Care is taken to ensure appropriate depth of dissection over the dorsum to avoid buttonholing the skin.

Next, the soft tissue envelope is freed from the bony dorsum with a periosteal elevator in a subperiosteal plane. This will allow for re-draping of the skin-tissue envelope as a single unit at the conclusion of the case. With the dorsum sufficiently exposed a dorsal cartilaginous pocket is created for flush placement of the butterfly graft. The thickness of the ear cartilage is typically about 2 mm, so a corresponding dorsal pocket of approximately 2 mm depth is created to allow for flush placement of the graft over the dorsum and smooth nasal dorsal contour.

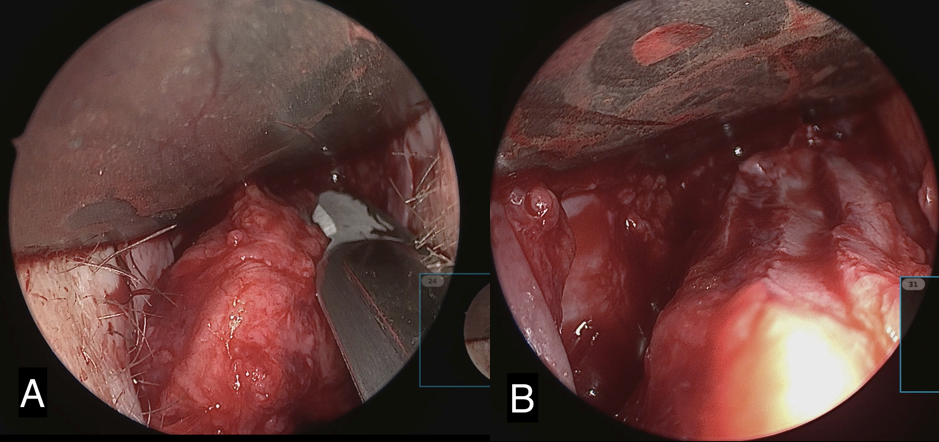

Excellent dorsal exposure is achieved by placing the converse retractor in the nasal cavity on the opposite side of the surgeon, with the flat end of the retractor angled back towards the surgeon. With the #15 blade, the cut is made towards the surgeon with care taken to stay in the same plane across the entire dorsum and not skive towards the skin as you progress with your excision. Successful reduction of the dorsum results in a pocket approximately 2 mm in depth with three parallel structures clearly visualized which are the trimmed edges of the right ULC, dorsal septum, and left ULC (figure 2 and 3).

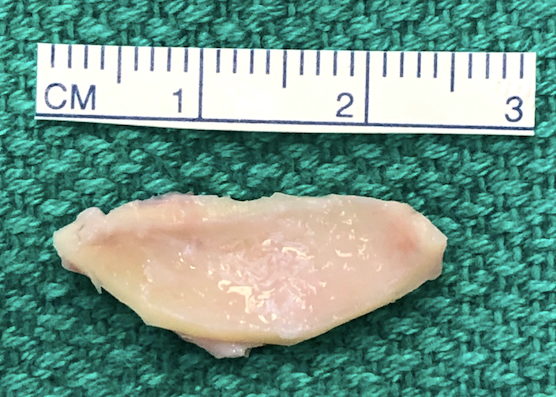

Next, the butterfly graft is harvested with enough length to span as far laterally on each side as necessary to correct the collapsed nasal valves. See below for description of graft harvesting. The graft is then trimmed at the edges and contoured. The superior edge of the graft is beveled to further reduce the risk of supratip fullness and allow for a smooth nasal dorsal counter (Figure 4). The graft is then placed in the dorsal pocket. If adequate dorsal reduction was achieved, the nasal dorsum should be smooth. Additional re-excision to deepen the dorsal pocket may be required.

Once the graft is in its final position, it is sutured in place with external flaring sutures. This technique requires help from an assistant and a few coordinated movements, but allows for improved lateralization of the graft during healing, thus further increasing the nasal valve angle and reducing its tendency towards collapse. While the surgeon holds one end of the graft to the upper lateral cartilage and nasal mucosa through the intercartilaginous incision, the assistant stabilizes the contralateral side with a non-toothed forceps as well. 3-0 nylon is used to suture from external, at the alar crease, to internal, penetrating the graft on the way into the nasal cavity. The suture is then thrown from internal to external, again penetrating the graft and exiting on the alar crease. The suture is tagged with mosquito forceps. This technique is then repeated on contralateral side. While throwing the second flaring suture, it is helpful to have your assistant hold the graft down at the dorsum. This maneuver eliminates dead space and the potential for dorsal puckering of the graft while throwing the second flaring suture. Next, a perforated splinting sheet (Aquaplast™, Patterson medical Supply, Warrenville, IL) is cut to fit over the external nose. The sutures are threaded through the perforations of the splinting sheet and again tagged with mosquito forceps. The nose is then cleaned, dried, and a layer of liquid adhesive (Mastisol®, Eloquest Healthcare Inc, Ferndale, MI) is applied. Half-inch paper tape is cut to size and layered over the external nose. Finally, the assistant uses the sutures to guide the splinting sheet into a cup of hot water. Once the splint softens, it is lifted from the hot water and the surgeon threads the splint down the flaring sutures onto the nose. Simultaneously, the assistance holds the sutures in a superolateral vector to mimic the desired final lateralized position of the graft to best counter dynamic nasal valve collapse. Once the splint has hardened the sutures are tied over the splint (Figure 5).

Ear cartilage harvest

Though harvesting of the cartilage comes from within the conchal bowl, the incision is placed laterally on the peak of the antihelix (Figure 6). This prevents post-operative webbing and cicatricial scaring. Additionally, the scar hides nicely on the natural peak of the antihelix. The conchal bowl and corresponding posterior auricle are injected with a 50:50 mixture of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 and 0.25% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine. The incision is made with a 15 blade to the cartilage. A freer or tenotomy scissor is used to establish the subperiosteal plane. The conchal skin is elevated off the cartilage dissecting medially. Soft tissue elevation is the performed on the posterior surface of the cartilage. The graft, measuring approximately 10 mm x 25-30 mm, is sharply excised from the conchal cartilage with a 15 blade and placed in a saline bath. Hemostasis is obtained in the wound bed, and the incision is closed with a 5-0 fast absorbing gut suture in a running fashion. A bolster is placed to eliminate dead space and prevent a post-operative hematoma. A 5” x 9” occlusive petroleum gauze is rolled and placed snuggly in the conchal bowl. A 3-0 Nylon suture is placed transmurally through the conchal bowl with a non-adherent gauze on the posterior auricle to protect the skin. Bacitracin ointment is applied to the incision and bolster.

Post-operative Care

Patients are discharged on the day of surgery. No antibiotics are indicated. Pain control is achieved with scheduled acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and a small number of low-dose opioid tablets for breakthrough pain in the first few days following surgery. Patients begin gentle nasal saline sprays on post-operative day one. Bacitracin ointment is applied to the conchal bolster and incision twice daily. Patients are instructed to avoid nose blowing, nasal manipulation, straining, heaving lifting, or strenuous activity for two weeks. Initial post-operative follow-up is schedule for one week, at which time the nasal cast and conchal bolster are removed. An additional post-operative visit at three months, at which time the NOSE scale is repeated, assess for continued healing.

Conclusion

Butterfly grafting is a useful technique in the treatment of internal nasal valve collapse (2,3,4). The endonasal approach remains a valuable approach as it provides adequate visualization while maintaining major nasal tip support mechanisms and limiting scar. Close attention to detail optimizes functional and cosmetic results of butterfly grafting. Careful excision of the native nasal dorsum and beveling the superior edge of the conchal cartilage graft reduces external graft visibility and supratip fullness. Placement of the external flaring sutures through the splinting sheet improves lateralization of the graft, and thus, further increases the patency of the nasal valve.

Resources

- Walter C. The use of composite grafts in the head and neck region. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1977;4(3):7-10.

- Clark JM, Cook TA. The ‘butterfly’ graft in functional secondary rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(11):1917-1925.

- Stacey DH, Cook TA, Marcus BC. Correction of internal nasal valve stenosis: a single surgeon comparison of butterfly versus traditional spreader grafts. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63(3):280-284.

- Friedman O, Cook TA. Conchal cartilage butterfly graft in primary functional rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(2):255-262.

- André RF, Vuyk HD. The “butterfly graft” as a treatment for internal nasal valve incompetence. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(2):73e-74e.

- Chaiet SR, Marcus BC. Nasal tip volume analysis after butterfly graft. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(1):9-12.

- Loyo M, Gerecci D, Mace J. Modifications to the butterfly graft used to treat nasal obstruction and assessment of visibilty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016:18(6):436.440.

- Fung E, Hong P, Moore C, Taylor M. The effectiveness of modified cottle maneuver in predicting outcomes in functional rhinoplasty. Plast Surg Int. 2014:1-6.

- Cafferty A, Baker D. Open and closed rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2016;43(1):17-27.